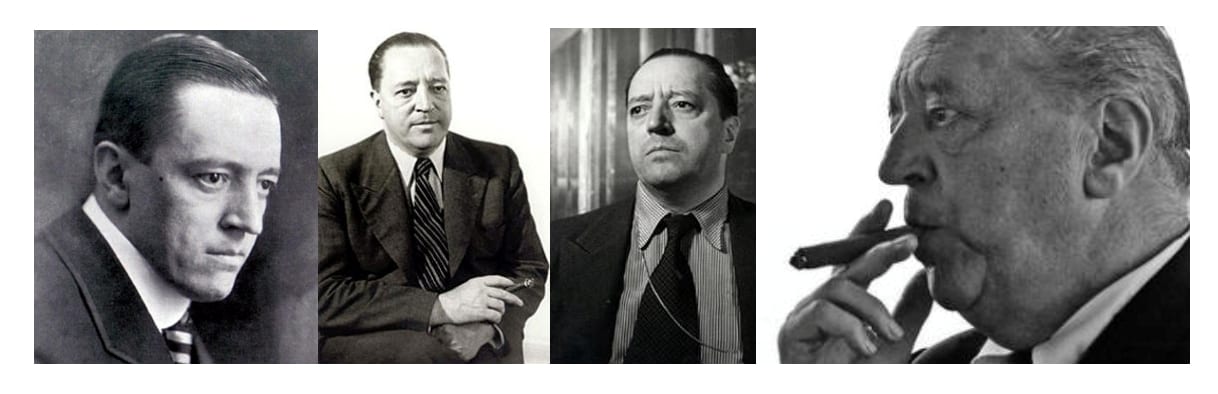

The skyline of Chicago would undoubtedly look very different without the contributions of architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

Alongside Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius and Frank Lloyd Wright, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe is regarded as one of the pioneers of modern architecture. He influenced an entire generation of architects and, during his 60-year career, established a design vocabulary that has helped to define mid-century modern architecture.

Commonly known as Mies, this legendary architect did not design buildings with a particular style in mind:

“I am not interested in the history of civilization. I am interested in our civilization. We are living it. Because I really believe, after a long time of working and thinking and studying that architecture…can only express this civilization we are in and nothing else,” he explained.

His stark, modernist structures were marked by straight lines, negative space, and a minimal use of colour – an expression of the era in which they were being built. His renowned ‘less-is-more’ approach does not just describe his work; it also encapsulates the manner in which he presented himself as a man.

Born in 1886 in Aachen, Germany, he came from humble beginnings. Working at his father’s stonemasonry business, he learned an appreciation of material and structure and then went on to become an apprentice with furniture designer Bruno Paul in Berlin. In 1908, without any formal architectural training, he joined the office of Peter Behrens, an architect and painter at the forefront of the modern movement.

After World War I, Mies joined the utopian artists of the Novembergruppe and founded the avant-garde magazine G (Gestaltung). He became one of the pivotal leaders of the architectural avant-garde in the early 1920s, producing visionary projects for glass and steel and executing a number of small but critically significant buildings.

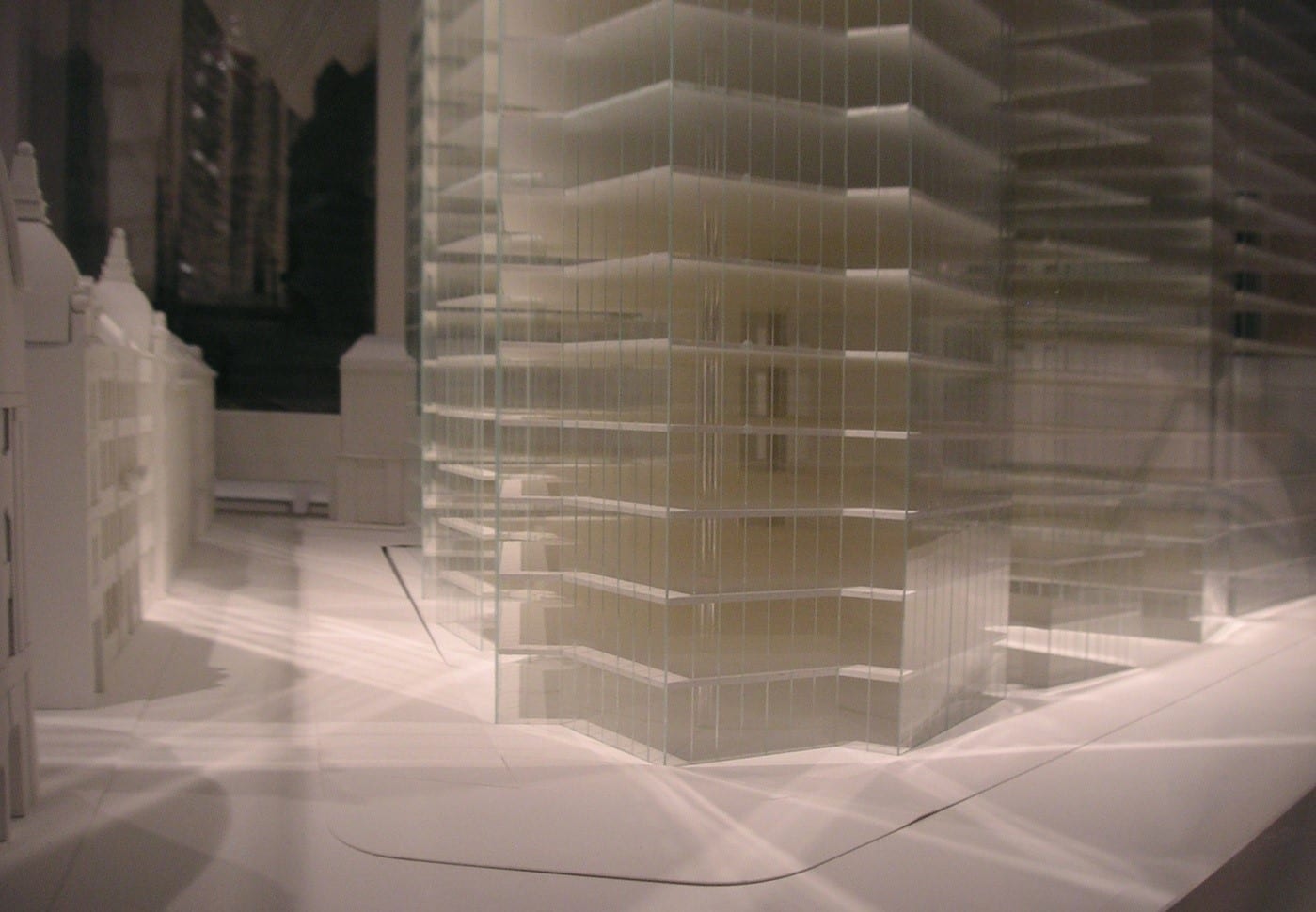

In 1927 his visionary design for the Friedrichstrasse Office Building, though never built, catapulted him to fame as an architect and it still remains one of the most important architectural structures in 20th century modern architecture. Mies’ vision for glass skyscrapers – crystalline, vertical facets of glass and suspended floor planes – came at a time when German expressionists like Bruno Taut and Hugo Häring were calling for a revolutionary architecture of transparency and organicism. Decades later, the skyscrapers Mies had envisioned began to dominate corporate architecture in America.

Photo credit: Jonas klock

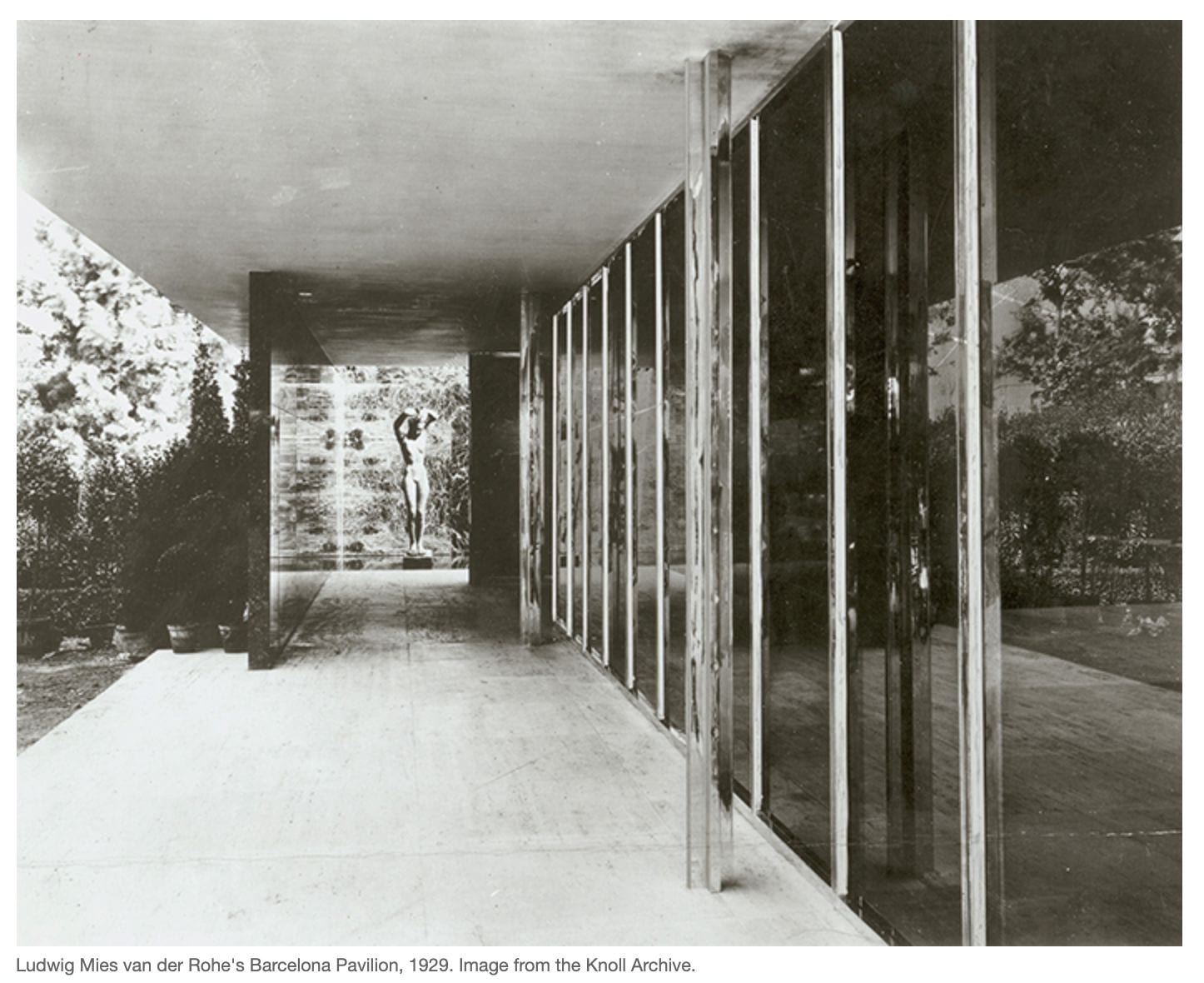

In the 1920’s Mies became heavily influenced by Dutch neo-plasticism, Russian suprematism and the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. Mies started to experiment with independent walls and ceilings. These experiments culminated in his most significant works, including the Barcelona Pavilion in 1929 – now one of the most recognized objects in the architectural history of modernism – and the Villa Tugenhat completed in 1930. At this time he joined the avant-garde Bauhaus design school as their director of architecture and started to adopt and develop their functionalist application of simple geometric forms in the design of useful objects until the Bauhaus was forcibly closed by the National Socialist government in 1933.

Due to mounting pressure from the growing Nazi regime Mies emigrated to the United States in 1937. During this year he met Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin – the meeting between these living legends was momentous. Mies had long admired Wright’s work and sense of spatial relationships; Wright respected Mies’ ability to temper usefulness with materials, fluid space with an original aesthetic.

Soon afterwards, Mies accepted a position as director of the architecture department at the Armour Institute of Technology, soon to be renamed as the Illinois Institute of Technology . At his inaugural lecture he stated:

“In its simplest form architecture is rooted in entirely functional considerations, but it can reach up through all degress of value to the highest sphere of spiritual existence to the realm of pure art.”

This epitomises Mies’ consistent approach to design – to begin with the functional considerations of structure and material, then to refine the detail and expression of those materials until they transcend their technical origins to become pure art with the expert use of structure and space.

In 1939, he began preliminary designs for the campus on the south side of Chicago. Its composition was one of low-slung rectangular buildings composed of steel and concrete frames wrapped in brick and glass curtain walls. Arranged as subtly juxtaposed figures this site became one of the most important examples of modernist urban design. The campus was revolutionary at the time – a perfect expression of Mies’ principles of design and well-known “less is more” approach.

During this period, Mies transformed what had been primarily a pragmatic construction technique for large buildings, the steel frame, into a refined art form in which the steel itself became one of the primary expressive elements. This involved moving away from the dynamic, pin-wheeling forms of his 1920’s works, and a return to a more severe classicism, with cubic volumes, often raised over carefully paved plazas and asymmetrically balanced against surrounding buildings. This classicism was interpreted through a radically modernist lens as seen with his use of transparent walls and continuous ceiling planes extending sight lines beyond the interiors in an attempt to represent infinitely receding space.

In 1960, Mies was awarded the AIA Gold Medal – the highest award given by the American Association of Architects. Considered among the greatest architects of the 20th century, Mies’ influence can be seen throughout Chicago and certainly reaches far beyond his adopted hometown. His many significant US projects include the residential towers of 860-880 Lake Shore Drive, the Chicago Federal Center complex, the Farnsworth House, Crown Hall, and the Seagram Building in New York City. Some of these are now considered canonical monuments of modernism and are studied by scholars and architects all over the world.

All of his projects are characterized by simplification of form and subtraction of ornament from the structure and theme of the building. Mies was clearly intrigued by the emerging technologies of the day, and used mostly concrete, glass, and steel in his revolutionary creations. His buildings radiate the confidence, rationality, and elegance of their creator and, free of ornamentation and excess, confess the elegance of simplicity.

In our time, where there is no limit to excess, Mies’ reductionist approach is as pertinent as ever and his influences can be seen in the design of Workagile’s Haag range that blends the beauty of raw steel and polished timber. As we reduce the distractions and focus on the essential elements of our environment and ourselves, we find they are intricate, and beautiful. As Mies’ always said: Less is more.

Continue reading the series:

THE MAGIC OF VICTOR HORTA – THE FATHER OF ART NOUVEAU ARCHITECTURE.