As we continue our exploration of 17th – 20th century architecture and investigate how the forefathers of modern architecture were motivated by the healing traits of biophilic and salutogenic design, we look at how the Art Nouveau architectural designs of the late 19th century were inspired by nature.

The Art Nouveau style grew out of a desire for a bolder, more futuristic form of architectural expression. It was meant to dazzle, shock and entertain and also tell us much about our connection to the natural world.

There is a plethora of examples of Horta’s handiwork across Brussels as he accepted commissions from wealthy industrialists and Freemasons, socialists and the Brussels city authorities alike.

Responsible for the Brussels Central railway station and the Belgian Centre for Strip Cartoons, Horta’s architectural legacy also included four town houses that are now Unesco-listed World Heritage Sites: Hotel Tassel, Hotel Solvay, Hotel van Eetvelde and Maison & Atelier Horta which are now regarded as iconic examples of Art Nouveau architecture. It is worth noting that none of these buildings were actually “hotels” as we know them today; rather, they were “hôtel particuliers,” an Old French term for a grand, free-standing townhouse.

Hotel Tassel

In 1893, Horta brought to life what is known as the very first Art Nouveau building: Hôtel Tassel. A refreshingly historic juxtaposition to the modern apartment complex that now sits across the street, the Tassel house has an extraordinarily unique floor plan. Originally built for the Belgian scientist Emile Tassel, it consists of three different parts: two brick-and-stone buildings that are connected by a glass-roofed steel structure inviting in natural light. The use of natural light and the open floor plans were fairly new at the time, as was his use of glass and iron in ‘botanical’ forms.

With detailed doorways, intricate wood panelling, and mosaic floors, Hôtel Tassel served as inspiration for Horta’s subsequent structures, Hôtel Solvay and Hôtel van Eetvelde.

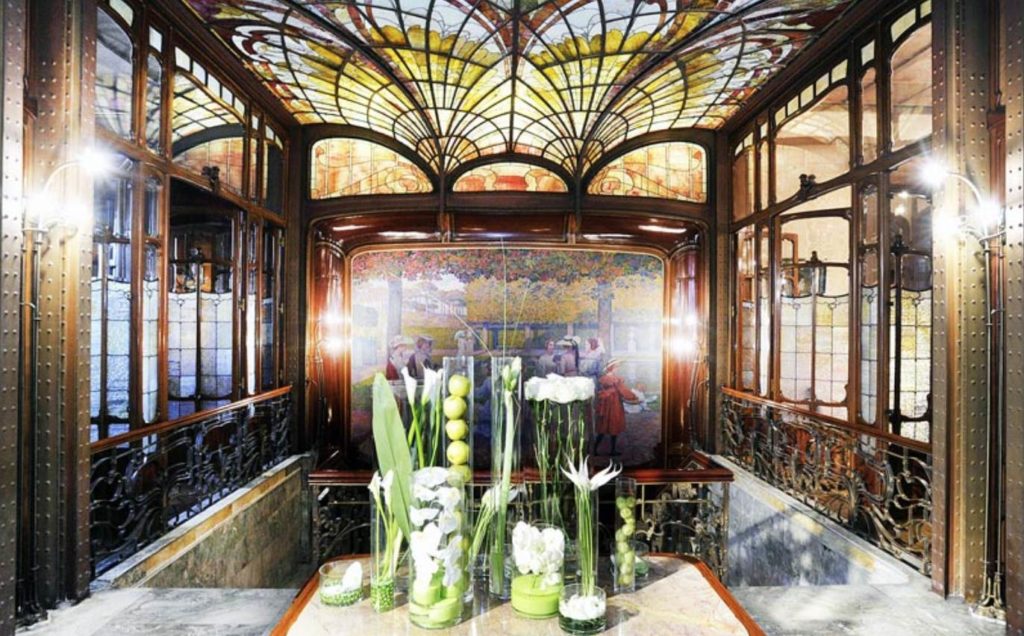

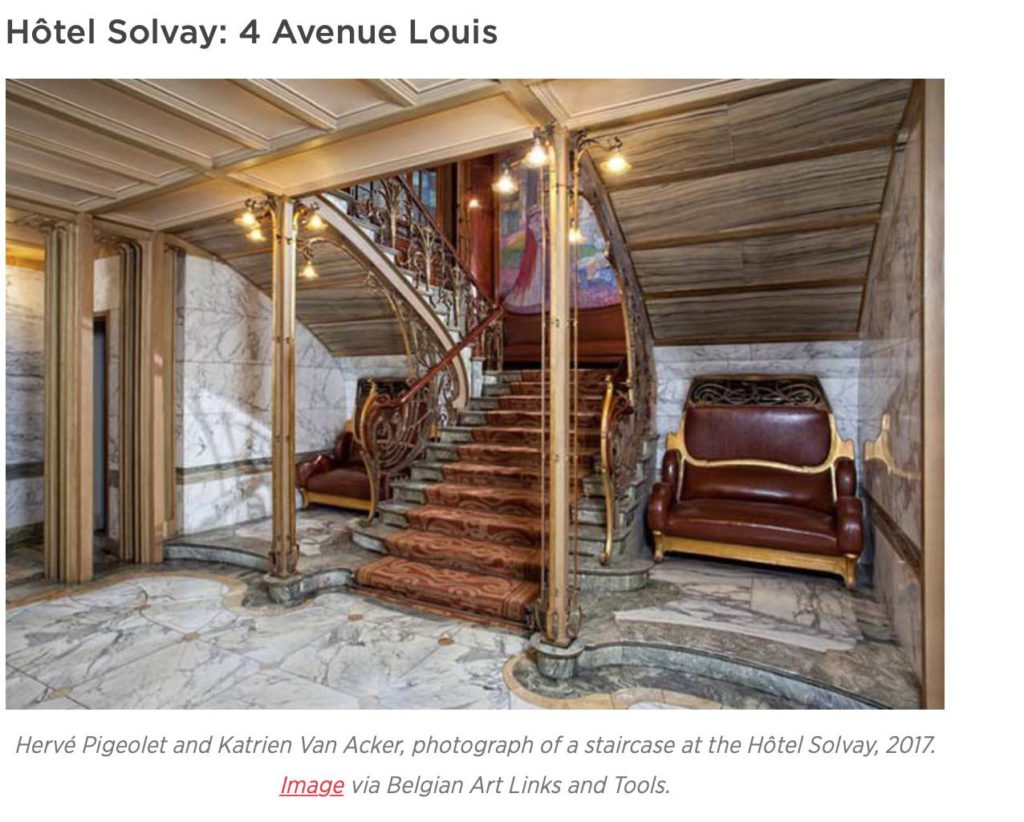

Hotel Solvay

Considered Horta’s most ambitious work, Hôtel Solvay was constructed just one year after the Tassel house in 1894. It was built for the leading chemist Armand Solvay, who gave Horta free reign to draw up a magnificent space for Solvay’s beloved wife. Like the Tassel house, Hôtel Solvay is equipped with a glass-covered central area, under which Horta designed a charming winter garden. He filled the home with his custom furniture and elegant wood and glass work, incorporating dashes of his signature somersaulting lines.

Hôtel Solvay is said to have fueled Horta’s rise to fame. He began to focus on “the innate vitality of people,” using new materials like industrial steel and glass to better the lives of his residents. In the Solvay home, Horta did this by allowing for a profuse, expansive filtering in of natural light.

Hotel van Eetvelde

The van Eetvelde House represents arguably the most daring and innovative of Horta’s residences in Brussels, built in two primary stages; the initial one from 1895-98 and an extension constructed from 1899-1901

Similar to Hotel Tassel, the significance of the building lies in its octagonal stair-hall – its metallic columns revealing the unusual industrial frame of the building. The combination of stochastic branching, the spiral of the staircase and the web-like decor makes it feel like the residents of the house are firmly embraced within mother nature’s arms

Branching out into flattened arches to support a large blue-green stained-glass ceiling, the lower portions over the staircase show off Horta’s exuberant, twisted curves that continue down into the balustrades; motifs that are extended throughout the furnishings of the house -the rugs, the fireplace and even the light fixtures work together to comprise a seamless work of art that acts as an oasis in an urban environment.

The modulation of light and shade as well as the tangles of vines and leafy foliage exploit and appropriate the natural imagery found often in the jungles of the Congo – the colonial territory that van Eetvelde administered.

Until the First World War Horta’s designs embodied and informed the emerging Art Nouveau style – his exuberant plant tendrils lacing through building can be found all over Belgium as he utilised iron, glass and steel in a flowering form of architectures that manifested itself in both exteriors and interiors. Among the terms used to described his style were biomorphic whiplash, curvilinear, organic and simply “the Belgian Line” In terms of sheer exuberance, Horta was renowned for his combined use of fractals and curves both inspired by the natural

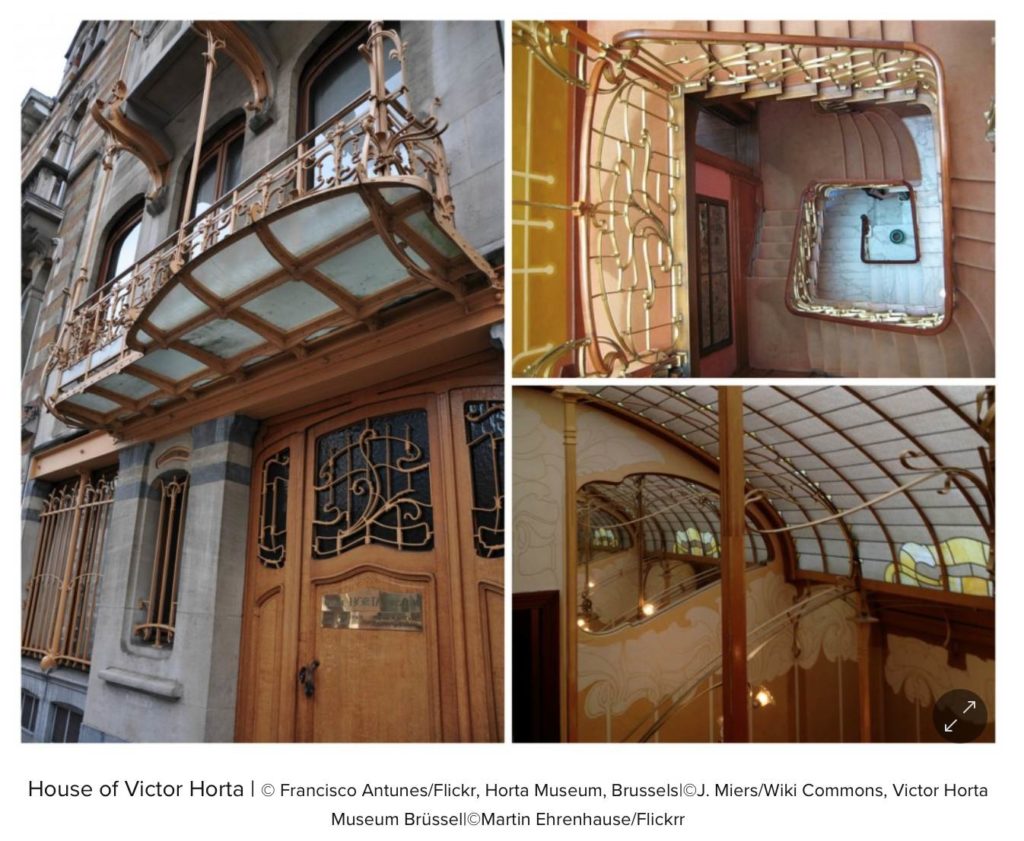

Maison & Atelier Horta

With its stone façade and delicately designed metal railings, Horta’s house is obvious to see on rue Americaine. Thought modest in size, the Maison & Atelier Horta are nevertheless a real showpiece of the creative capacity of Victor Horta – a laboratory where he experimented on the combination of materials and spaces with the most up-to-date technology.

The ensemble has three floors and a mansard roof, the most spectacular element in the building is represented by the vast glass ceiling over the main staircase where structure and decoration are closely linked, forming a single element. This end destination for the branches are attractor points; a fractal concept where the forms cascade from the whole to the parts

Horta’s break with classicism is not only related to aesthetics, but also to demonstrate the way of life and the sensitivity of the bourgeoisie. The basic inspiration of modernism comes from nature, which is reflected in every detail of the décor and every detail is well thought-out.

Here you can find a supreme example of Horta’s desire to infuse every part of a dwelling with the principles of “New Art”; to create interiors that were “full of light, enthusiasm and energy” From its wrought-iron swirls and glazed brickwork to its cleverly crafted built-in wardrobes and Japanese-inspired cloakroom, down to its mahogany doors with ornate handles and its “whiplash” curves and stained-glass splendours, the building has plenty of admirers. Horta relied on curvature and ornamentation to trigger the healing effect of biophilic design. The museum is filled with Horta’s own handmade, beautifully crafted furniture and other decorative art. Through the rational use of metallic structures, Horta conceived flexible, light and airy living areas – directly adapted to the personality of their inhabitants. This stylistic revolution is reflected by the open plan layout and diffusion of light throughout the construction.

Echoes of Horta

Because of the originality of his works, he inspired other architects and artists. There are echoes of Horta in some of Antoni Gaudí’s fanciful creations in Barcelona; the French architect Hector Guimard transposed ideas displayed in the Tassel house to his designs for the station entrances of the Paris Metro. At the Horta Museum the work of contemporary artists is often showcased based on the quality of craftsmanship and a connection with Horta’s style of work. Nacho Carbonell’s organic curved furniture was inspired by an idea to view objects as living organisms – a fitting complement to Horta’s way of bringing structures to life with natural motifs sunlight and movement. With his inspiration from nature, experiments with colours, textures, dynamic and organic lines and forms and playfulness with light and shadow, Horta’s style is as relevant to designers today as it was then.